There’s no doubt that council housing has a bad rap, seen as a series of concrete towers falling down under the weight of mismanagement and disrepair. Occasional guest appearances on TV crime series haven’t helped. But the mood is changing. Local authorities are investing in new structures; blogs such as Municipal Dreams are celebrating our housing heritage, and one scheme has been awarded architecture’s top prize.

So come on, let’s celebrate what’s been built! We’ve come up with the definitive list of the most iconic and successful public housing in the UK covering the last 114 years. Marvel at some of the gems on display in our all-time top 10. And don’t forget that our grading is based on how the buildings meet the needs of the residents – not just those of the architects picking up the awards.

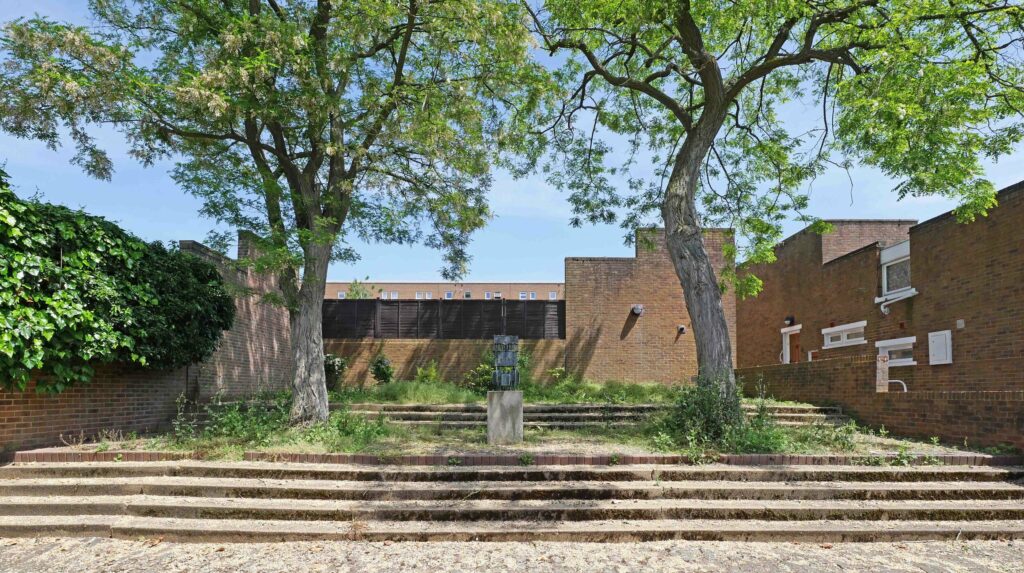

1. Goldsmith Estate

Norwich, 2019

One of the interior courtyards in the Stirling Prize-winning Goldsmith Estate, designed by architects Mikhail Riches

A recent addition to the social housing roster, this development sits right at the very top of our list thanks to the outstanding build quality, plus a factor that has been until recently has been overlooked – eco-friendliness.

The people behind Goldsmith Estate took home the Stirling Prize in 2020 – British architecture’s leading award – thanks to so much good design. Notably, attractive beige brick that curves round street corners, hidden patios and perforated design. Roofs are angled so that the sun can reach windows of the row of houses behind. It hits Passivhaus standards, the German voluntary code, with a 70% reduction in fuel bills for residents. Passivhaus also requires windows to be raised one metre from the ground – a great height for a window seat, as it happens.

In recent years, national government restrictions on reinvesting funds from sales of council houses into new buildings has impacted building. But Norwich City Council has found a way. Through a mix of borrowing, taking money from a housing revenue account and dipping into reserves, they were able to bring in Mikhail Riches and Cathy Hawley. And the architects created streets rather than apartment blocks, modelled on the network of Victorian terraces in Norwich city centre, instead of the high-rises in this part of Norwich. With space for bikes and prams and parking pushed to the edge of the development, this is housing of the future, and a blueprint for others to follow.

2. Boundary Estate

Tower Hamlets, 1910

The oldest, possibly the best looking, and almost the top-scoring estate on our list, this classic late Victorian development was born in the wake of the Housing of the Working Class Act. London County Council commissioned Owen Fleming to improve on the slums in the area and he designed wide, tree-lined streets radiating from a central bandstand. Fleming also drew in the striking lines of bright red brick and cream stone that run across the blocks, lightening the sheer heft and weight of substantial five-storey structures. They rise up to completion in a mass of chimney stacks and gables, delivering chunky Arts and Craft appeal.

As a work of architecture, the Boundary Estate stands out amidst the 1960s tower blocks often associated with social housing. Grade II-listed and elegantly designed around nearby schools and churches, it has all the attributes to make it our number one. Except for its rather checkered history. At the time of inception, many of the poor inhabitants were kicked out to allow more affluent working class inhabitants to move in. Which is not exactly in tune with our social housing ethos. Today’s iteration has a community-run laundrette on site, plenty of green space and an arts centre, almost as if it’s trying to make up for past ills. There’s also the fact that 40% of flats are now privately owned – a location next to Shoreditch and the City has driven this. In fact, a local estate agent would describe a wealth of amenities and a prime location – if it wasn’t for the fact that the Boundary Estate is still – just about – a social housing project.

3. Trellick Tower

Kensington and Chelsea, 1972

This monument to modernity rises sharply out of the west London landscape, with a separate service tower completing the iconic silhouette that’s repeated on so many T-shirts and album covers. Designed by Ernó Goldfinger, a Hungarian-born emigré whose name also provided the inspiration for a James Bond villain, it was built in the Brutalist style that dominated social housing in the 1960s. Goldfinger was one of a number of Eastern European architects to move to the UK, and came late to Le Corbusier-style urban living in the sky – just as it was falling out of favour. The 1980s quickly turned the Tower crime-ridden and deprived, with threats of demolition by the local authority.

Yet for residents there was another world. The stairwell mixes bright stained glass with hammered concrete, casting a soft, coloured light over public areas. Large apartments and balconies provided stunning views across the capital. Now loved and gentrified, as well as Grade II listed, the difficult history of Trellick Tower is recognition that as with nearby Grenfell, structures like this are widely open to abuse.

4. Challender Court

Bristol, 2018

Challender Court showing balcony areas designed to provide plenty of light but also limit overlooking of neighbours

A development that proves you don’t have to be huge to have an impact, with eco credentials and build quality that has impacted local authority housing departments and designers in just a few short years since.

Created by Emmett Russell architects, Challenger Court is part of three social house projects in Bristol. It’s small by the standards of other entrants in this list, with just eight one-bed apartments. But with a generosity of space in each flat – around 50m2 each – and sensitively incorporated into nearby housing, this development stands tall. Large windows convey plenty of light, while slated metal balconies in front of them minimise overlooking of other residents. A carefully placed rill helps with drainage. As with Goldsmith Estate in Norwich it’s built to Passivhaus principles, using heating from natural, or ‘passive’ sources: triple- insulated windows, the sun and even the human inhabitants of each flat. Unlike some concrete incarnations of social housing, Challenger Court is built to last, finished off with a light brick and powder-coated aluminum exterior built to improve with age.

5. Brunswick Centre

Camden, 1972

The iconic angled shape of the Brunswick Centre, creating angled windows that capture extra light in facing rooms

Once described as “a rain-streaked, litter-strewn concrete monstrosity that seemed destined for the bulldozer” by writer Steve Rose, in 2002 the grade II-listed Brunswick Centre was brought back to its original brutalist glory. A £22m restoration then has led to a gradual improvement since – so that it is now the vibrant shopping and dining centre once envisaged.

The origin story of the Brunswick Centre is one of limited circumstances leading to a very creative solution. Back in the early days of the site, a developer had wanted to put in a couple of high-rise towers but was thwarted by London County Council not permitting buildings higher than 80ft. So he turned to Patrick Hodgkinson who, inspired by Finnish architect Alvaro Alto, opted for banked ramparts to provide the same density as the tower blocks. The developer also failed in getting enough buyers in time, so apartments were leased to the London Borough of Camden, who took over residential management.

Living quarters aren’t huge, but they’re light-filled thanks to the classic angled windows. It’s a fabulous location, near Russell Square in central London. On the downside, 100 of the 400 flats are now privately owned, and the slightly uneasy relationship that exists between the landlord and the council-owner continues. That drops Brusnwick a few places down our list. But as a place to live and also visit – or even catch a film in the local cinema – it scores highly.

6. Bishopsfield

Harlow, 1967

Designed to imitate an Italian hill town, locals saw this estate instead as something you might find on the other side of the Mediterranean, hence frequent references to the ‘kasbah’. But behind this name-calling was a valuation of the low-rise, human proportions of the development, with alleys and courtyards winding their way through the Essex countryside. So in 2008 when faced with demolition, 92% of residents argued against its removal. The striking cuboid structures contain ‘L’-shaped flats of between one and five bedrooms arranged around a courtyard, with parking restricted to certain areas – something that is only now being introduced into new developments. Michael Neylan and Bill Ungless created a rarity, a modern structure that was loved, and ahead of its time.

7. Byker Wall

Newcastle, 1983

The sharply rising edifice of Ralph Erskine’s Byker Wall protect inhabitants from local noise and weather

A long winding wall of 620 maisonettes housing 9,500 people, this was architect Ralph Erskine’s crowning glory and a break with the Brutalist orthodoxy of the time. Started in 1969 and finally completed in 1983, the development stands out not just for its incredible 1.5 mile structure, but also the range of textures and colours from the use of different bricks, terraces, balconies mixed with private gardens and larger open spaces. The wall that forms the key part of the design was intended to block out noise and pollution from a motorway. This was never built, but the structure functions as a useful barrier to North Sea winds. Lack of funds meant poor construction and materials in some areas, but overall it is a design classic, as recognised by UNESCO when they placed it on their outstanding twentieth century buildings list.

8. Windmill Estate, Ditchingham

Norfolk, 1948–63

Modern terraced housing in Tayler and Green’s rural, more spacious take on the traditionally city-based form

A beneficiary of the post-war boom in social housing, when half a million homes were destroyed or made uninhabitable and 3 million were impacted by bombing, Windmill Estate wasn’t replacing a load of inner city rubble, however, but being built in rural Norfolk.

Loddon Rural District Council turned to Herbert Tayler and David Green amidst the housing shortage. Keen to make housing that fitted the location, not transplant yet more semi-detached from suburban settings, the two architects produced a 30 house-design that was horseshoe-shaped around a large green space, including bright, airy south-facing living rooms. It was terraced, a form not seen in the countryside since the 18th century. This meant saving on building costs, but also a simplicity of form and ease of navigation. There were small touches too, such as the date of a building marked by different coloured bricks embedded in a side wall. According to Tayler: “people do like decoration”. Windmill Estate is modernity without austerity – and a recognition that little details make a place liveable.

9. Mackworth Estate

Derby, 1959

This development edged into our top 10 because of what so many planners often miss – amenities. Schools, shops, recreational spaces, churches cater for the needs of residents but also provide spaces to people to meet up. Roads curve in crescents with a few cul-de-sacs amidst an array of footpaths. Houses are semi-detached or in short terraces, with variation provided by occasional pebble dash alongside red brick. There’s a demographic mix, with three-bed dwellings for houses alongside bungalows intended for the elderly. Overall out of 1,642 dwellings, 200 were built for private sale. This estate was created during a period of optimism, when despite straightened public finances, somehow places such as this were built. And amidst all the current difficulties, some of that spirit could be returning.

10. Park Hill

Sheffield, 1961

The brutal geometries of Sheffield’s Park Hill estate, which has had a recent influx of businesses and residents

Towering over Sheffield city centre, for some people this high-rise housing estate was representative of everything that was wrong with the inner city renovation projects of the 1960s. Part of the Brutalist phase of British architecture that included Birmingham’s Bullring and Trellick Tower (see above), Park Hill was designed as a mini-city on the hill that materialised as a monstrosity on the mound for those who disliked its design and dominance. Created by Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith, Park Hill was meant as a utopian vision of how to live. And it succeeded to some extent, with neighbours from previous slums rehoused next to each other, a local nursery and homes for a 1,000 people built. Meanwhile, a striking Mondrian-esque aesthetic in its frontage knitted buildings together. Given listed status by English Heritage in 1998 and a makeover by Mikhail Riches, a shortlist for the Sterling Prize in 2024 resulted. Now a mix of student accommodation, privately owned and affordable housing, and some social housing, it’s a diluted utopia. But the impact of such a dominant part of our social housing history is not in question.

Thanks for reading our top 10. As you’ve seen, it’s based on intersecting matrices of architecture, amenities and historic impact, with some weighting towards eco-friendliness bearing in mind what the future might bring. Putting those together was a lot of fun – and gave us a final list. It shows what value there is in social housing. Because when you can build this well, despite right-to-buy and successive policies over the past 40 years, there’s still hope.