Based on the latest government figures from March, here’s the latest on how the industry and government are progressing in their attempts to make our high-rise properties safe.

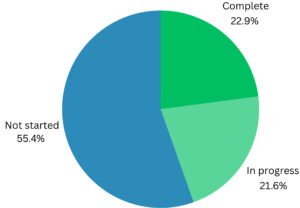

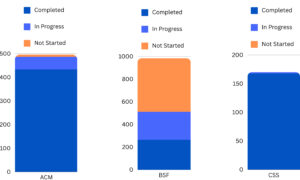

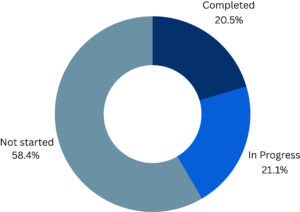

It’s an overall summary of where we’re at, with 22.5% of buildings repaired, 23% with work underway on making the building safe and 55% where projects have not even yet started.

The bald truth is that remediation is on the low side, with the exception being the more high-profile ACM scheme. Here the obvious threat of publicity has driven reform, but elsewhere progress is slow. The data makes that clear, with the major schemes and industry sectors covered in our summary. Check it all out below, starting with our charts showing remediation started, in progress and not yet started at all.

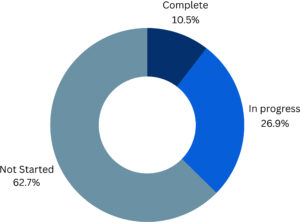

Social Housing

The proportion of cladding works started is even lower in the social housing sector, with an even smaller proportion completed here – 10%. A sizeable amount – 63% – has not even begun work.

ACM

Given that this covers high-rise residential buildings with the most dangerous type of cladding – such as that formed part of Grenfell Tower – it is perhaps not surprising that most progress has been made under The ACM Cladding Remediation Programme. This has been monitoring buildings since 2017. A total of 87% of buildings have been re-cladded, with only 2% yet to start remediation.

Building Safety Fund

This scheme is for buildings over 18 metres, which have different types of cladding to that included in Grenfell but which are nonetheless deemed dangerous. That, along with the fact the scheme began in 2020, three years later than ACM, explains the sudden drop-off in a completion rate of 28%, with 26% having started remediation. That leaves a sizeable 46% of buildings with no remediation work started on them at all.

The Cladding Safety Scheme

This only opened for applications in July 2023. It also only covers buildings higher than 18 metres outside London. That partly explains the rate of progress, with only two buildings having work begun on remediation. However, there are plenty in the pipeline, the government insists.

Developer Remediation

Life-critical fire safety defects have been found in 1,501 buildings, and developers have committed to remediating these. However, 58% of these buildings have yet to have any work instigated, with just 20% completed to date. From a severity point of view, this is comparable to ACM but the completion rates are not.

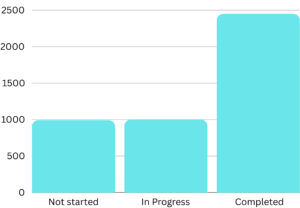

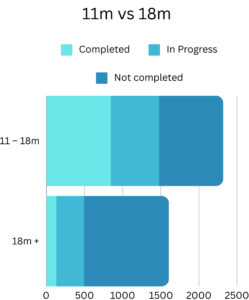

11m v 18m buildings

It’s notable that there has been less progress in the higher category building above 18 metres, with 8% at this height having their cladding remediated. This compares to 31% in the 11–18 metres band. In fact these taller high rises have just 69% not yet even started.

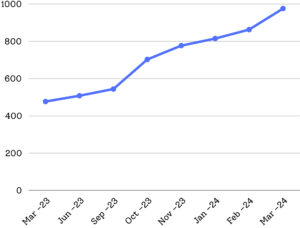

Progress over the past 12 months

This shows how much work has been done in the past year on cladding remediation. It portrays a gradual rise in remedial activity, with a recent increase after being almost flat over the winter months.

That’s our roundup of the top stats that have come out of the government covering changes made to higher-risk buildings in the UK. We’ll update later in the year when hopefully we can show not just an increase in completed projects, but that the rate of progress has also increased.

All figures taken from UK Government, ‘Building Safety Remediation’ data, March 2024